Tax havens screwing the scrum on FDI data

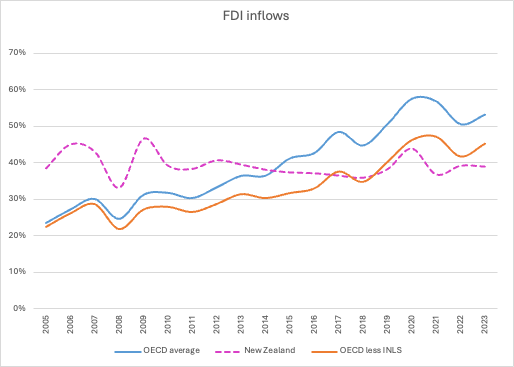

Removing tax havens from the OECD FDI inflow data appears to suggest that the impacts of NZ's restrictive FDI regime may not be as significant as first thought.

Yesterday David Seymour announced changes to our overseas investment regime. The main focus of those changes are speeding up the investment decision process and giving LINZ greater scope to approve decisions without Ministerial oversight.

Within an hour, BusinessNZ CE Katherine Rich had posted on LinkedIn with some OECD data showing that NZ had the most restrictive investment regime in the OECD, and that NZ FDI rates had fallen behind the OECD average since about 2015.

I took a look at the latest OECD data and had a play around.

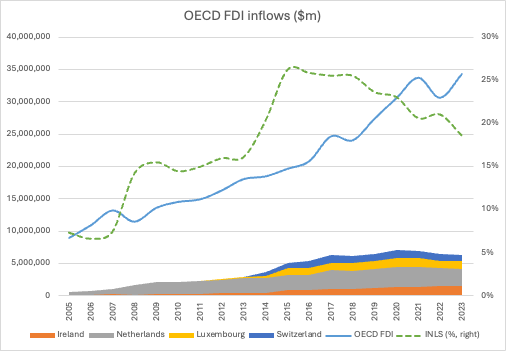

The first thing I noticed was that two notorious European tax havens - Luxembourg and Switzerland - only started reporting FDI data in 2012 and 2014 respectively, and there appears to have been some teething issues in that reporting.

Figure 1 shows Luxembourg’s FDI inflows jump substantially, from US$181.2 million in 2013 to to US$1,094.6 million in 2015, a 504 percent increase in just two years. From 2015 to 2021, Luxembourg’s FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP was above 1500 percent (measured on the right hand side of Figure 1), declining slightly to around 1300 percent in the latest two years for which we have data.

While Luxembourg has a relatively low headline corporate income tax rate, many multinationals have struck arrangements with the government that enabled them to reduce their effective tax rates to as low as one percent.

Switzerland and Luxembourg aren’t the only tax havens within the OECD data.

Ireland dropped its corporate tax rate from 40% in 1995 to 12.5% in 2005, and subsequent, while further changes to withholding tax rates on foreign income in 2010 made it even more attractive (the end of the so-called “Dutch sandwich”). Its FDI inflows have been around 250 to 350 percent over the last decade, see Figure 2

The Netherlands has similar FDI inflow rates, and its total inflowing FDI - just below US$3 trillion in 2023 - rivals the United Kingdom, whose population is almost four times as large.

The Netherlands and Ireland are both used by multinationals to substantially reduce taxable income from right across their global operations (including from New Zealand).

According to EU Tax Observatory’s 2024 Global Tax Evasion report:

the largest profit shifting destinations appear to be Ireland and the Netherlands, with over $140 billion shifted to each in recent years. In 2019, these two countries each accounted for approximately 15% of the total amount of profits shifted globally.

By 2015 Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Switzerland together accounted for 26 percent of total FDI inflows in the OECD (see Figure 3), but only 4 percent of GDP.

Removing these four countries from the GDP and FDI inflow data has a pretty substantial effect on how NZ sits alongside the adjusted OECD average, as we see in Figure 4 below.

The OECD average does conclusively exceed NZ FDI inflow levels in 2019, however they stay within a couple of percentage points of each other in subsequent years.

Jumping back to Figure 3 for a moment, the share of FDI inflows to Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Switzerland appears to peak around 2015 to 2017, before declining to around 17 percent of the OECD total in 2023.

This is probably the impact of the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act 2017, which reduced the US corporate tax rate from 35 to 21 percent, and gave major concessions to US multinationals that repatriated otherwise untaxed profits brought back into the country. Given US multinationals were major users of the tax benefits provided by countries like Ireland and the Netherlands, it’s unsurprising that returning FDI to the US was a viable strategy.

It’s hard not to see this as multinationals jurisdiction-shopping, moving investment around based on whoever has the lowest tax rates and most comprehensive secrecy regimes. And, while corporate tax cuts may entice investment in certain circumstances, as we’ve seen in countries like Ireland and Netherlands, those countries have obvious other advantages that New Zealand don’t, particularly proximity to other large consumer markets.

NZ may have a relatively restrictive FDI regime according to the OECD openness measures, but if we remove the tax havens from the data then we seem to be pretty much in line with the average level of FDI inflows. The reason for this - which I will go into somewhere else - is probably because the returns are pretty damn good. In other words, once you’re through the door, it’s party time.

What we can’t guarantee, however, is that we’d be able to capture the benefits of corporate tax cuts here.

What would you propose to be the optimal rate of company tax in NZ?